Image courtesy of Future of Personal Health

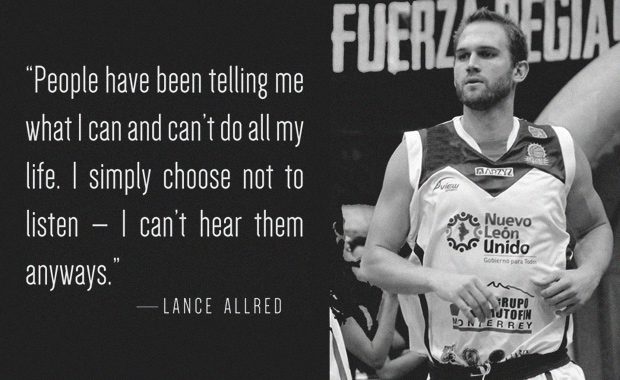

Jeffrey Kee: Lance, you had a very unorthodox upbringing. Born in Pinesdale, Montana, you were raised in a Mormon polygamist commune that your grandfather founded in the 1960’s. Describe your childhood and what it was like growing up in a community that practiced polygamy.

Lance Allred: It definitely was a very unique childhood that I wouldn’t trade for anything. It was the only life I knew, so why would I want it to be any different? My grandfather, Rulon Allred, who founded the Apostolic United Brethren, AUB, was assassinated 4 years before I was born. I never knew him, but I was raised in his “Utopian Dream.” There are, though, inconsistencies in such ideals. I learned at a young age that true socialism will never work because different people have different sets of work ethic and entitlement.

The good thing about growing up the commune was that I had all these cousins – I have over 400 first cousins and we were all running around like Smurfs in the wilderness there in Montana. That gave me a sense of “belonging” that was very addicting. That’s also the one thing that made it very hard to leave; feeling that everyone knew you and had your back was one of the draws of that culture. That being said, people won’t remain in cults or communes like this if they aren’t benefitting from it because there’s a dark side to these things as well. There is a lot of religious and psychological abuse – abuse of power, especially in these societies. Sexual abuse happens in these sorts of cultures because they’re so far removed from ancient society, government oversight and child welfare organizations. It’s a sad truth. Stereotypes are stereotypes for a reason and that’s because they’re mostly true.

JK: At the age of 5, you stated that your Sunday school teacher had convinced you that “God had made you deaf as a form of punishment.” Early on, what type of physiological effect did your disability have on you? And, despite towering over kids your age, were you bullied because of your deafness?

LA: This affected me greatly, at least, subconsciously. It is amazing how so many of us go through most of our lives unaware of the conscious and subconscious thought patterns that drive us and create a perpetuating reality. The story that I had been told as a little boy – that God made me deaf – created a huge, huge chip on my shoulder. Sadly, it told me that I had to earn love. I went through my entire adult life believing that if I became the first deaf player in NBA history, God would finally be proud of me. I wasn’t until I was 33 – when my son was born – that I learned that if love isn’t unconditional then it’s not love at all.

Growing up, I placed a lot of pressure on myself. When I was six, my family and I moved to Utah, as there were two headquarters at the AUB group – one was in Montana and the other was in Utah. Moving there was culture shock. I went from living in a nice commune with all my cousins and friends to living in the big, bad secular world of Salt Lake City, Utah as a first grader who talked funny, had these big giant hearing aids and was one of the biggest kids in the entire school. I was a big target of bullying; a huge target. Because of this, I developed a very quiet and introspective personality. I was very shy. I really didn’t talk to girls at all. I pretty much kept to myself, went home and played Nintendo with my brother or played with my dog; waiting for the weekends when I would get to play with my cousins around the Salt Lake Valley area.

JK: You didn’t start playing organized basketball until you were in the 8th grade, yet, four years later, you were named Utah’s 1999 Gatorade Player of the Year and were one of the most highly coveted seniors in the nation. Talk about your improbable rise to basketball stardom and why you decided to pick up the game at such a late age.

LA: When I was 12, my father discovered that several of our leaders had been sexually abusing their kids for years. Shortly after, my family broke away and escaped. We actually had to go into hiding as we fled our home, but eventually settled a few months later in downtown Salt Lake City right next to the University of Utah.

During the 8th grade, I grew from 5’10 to 6’4. I was a new school and had no friends, so as a good way to fit in and make friends, I started playing basketball. Before this point, I had never played organized basketball; I actually wasn’t very good at all. But again, with that chip on my shoulder, I believed that I had to earn love, so my drive to be good at basketball was very strong. I truly believed, in many ways, that I was playing for my eternal soul. Like I said, I thought that if I became the first deaf player in NBA history, God would be proud of me. That gave me a relentless work ethic. I was brutal on myself. Nothing I did was ever good enough. I became so focused and self-absorbed with my own neurosis that I had no idea how good I had become because I never allowed myself to feel safe and secure. It actually blindsided me. Out of nowhere, I began receiving college scholarship offers and then won [Utah’s] Gatorade Player of the Year.

Image courtesy of Lance Allred/Facebook

JK: After high school, you played at the University of Utah for two seasons before transferring to Weber State where you became a star. As a senior, you ranked 3rd in the nation in rebounding, were named first-team all-conference and had your Wildcats within two points of a Big Sky Conference title. Looking back, what was your best memory from your collegiate career?

LA: My career at the University of Utah was very dark. It was a dark time to say the least. I ended up transferring to Weber State University, which was a great fit. Coach [Joe] Cravens was an amazing mentor to me. My senior year, I led the nation in rebounding for most of the season. When we lost to the University of Montana by 2 points in the conference championship game – my season was over. At that point, I was leading the nation in rebounding with 12.0 rebounds a game, but Paul Millsap and Andrew Bogut both wounded up passing me in the postseason with 12.1 and 12.2 averages.

So, when things were beyond my control, I went from first in rebounding to third. Sometimes I ask myself, would it have made a difference if I had been the No. 1 rebounder that year and that would that have allowed me to be drafted? I don’t know. I don’t think so. Because at the end of the day, people were still going to say that Weber State University was a lowly school and didn’t have much competition. Then again, Damian Lillard went to Weber State.

The thing I miss the most about my collegiate career is, for sure, the friendships I made. At the time, I was still somewhat of a kid. You think you’re this old adult when you hit 21, but you’re still a kid and you’re still able to have fun because life hasn’t thrown you its best punches yet. So I guess the naïveté is what I miss the most.

JK: On March 13, 2008, nearly three years after leaving Weber State, you were signed by the Cleveland Cavaliers – becoming the first legally deaf player in NBA history. Describe the feeling of throwing on a Cavs jersey for the first time and achieving your childhood dream of being recognized as one of the most esteemed basketball players in the world.

LA: When I was in 8th grade, I started writing down my goals and throughout the next 13 years as my goals constantly matured and evolved. I always wrote down, “I Lance Allred will play in the NBA.” Every goal I had set for myself has come true, in some shape or form.

After college, I went through a crazy first year over in Europe and then after toiling in the D-League for some time, I eventually got my footing and the platform to really showcase what I can do with the Idaho Stampede. From there, I was called up to the Cleveland Cavaliers, which was a huge, huge euphoria. It was something that I had to set out to do. I had overcome insurmountable odds. So many people told me I’d never reach that level, so there was a lot of gratitude for that moment and that experience. When I put that Cavaliers jersey on for the first time and went out on the court, it was such an unbelievable feeling. But shortly after, the euphoria faded. Making the NBA had not been what I expected it to be. I didn’t feel any different. I didn’t feel that God loved me in some greater way, which allowed severe depression and disenchantment to soon settle in.

Image courtesy of Lance Allred/Facebook

JK: That 08’ Cavaliers team featured a number of experienced veterans – Zydrunas Ilgauskas, Wally Szczerbiak, Eric Snow and Ben Wallace to name a few. At age 27, were you still subjected to rookie hazing? If so, what type of treatment did you receive?

LA: I loved my teammates with the Cavaliers. They were actually very friendly. They were more kind of me than I ever expected them to be. There was a certain level of respect they extended towards me because most NBA “lifers”, who have seen so many teammates come and go, understand that so much of the business is luck and timing – being in the right place at the right time.

Is your agent a former teammate with the general manager of this team? Does he have several clients on that team that will help get you on? It’s a very political world. The mature players knew that for me to come up to the NBA from the back door [the minor leagues], so to speak, was, in fact, a very hard thing to do.

I didn’t receive much hazing from my guys with the Cavaliers. Sure, I’d have to carry bags, get the newspapers and bagels, or sing “Happy Birthday.” But, at the time, I was 27-years-old and had been through everything, so it wasn’t a problem because I had thick skin. If you’re too insecure to sing ‘Happy Birthday’ to somebody, you won’t last long in the NBA.

JK: Undoubtedly, LeBron James is one of the most polarizing players, both on and off the court, in NBA history. Having played with him for one season in Cleveland, what was he like behind closed doors?

LA: I actually enjoyed playing with LeBron. It’s a funny thing talking about LeBron because, as humans, we tend to want to view things in a very black-and-white, simplistic context. But let’s compare LeBron to Stephen Curry:

LeBron is very polarizing and part of that is because he’s so naturally gifted. He’s Superman. Most people don’t like that. They don’t think it is fair and are jealous because of it. Whereas, in Steph Curry’s case, because he’s such an underdog and had to work so hard and develop his athleticism when he got to the NBA, people like to root for him because he was an “underdog” from a small school. Don’t get me wrong- I love Steph Curry. I am just trying to create some context.

Now, when LeBron is laughing, having a good time, playing around and winning, people think he’s rubbing it in and being arrogant. But when Steph Curry is doing the same, people think he’s just a sweet kid; that he’s enjoying himself. So you see there’s a double standard that LeBron deals with that is sort of unfair, but as the saying goes: Where much is given much is required. I always tell people that LeBron, with his background and where he came from – the support he had growing up – pales in comparison to solid home life that Steph Curry had. So LeBron coming out of high school with all that money and fame thrown his way has done an incredible job. Most people have to realize that he’s one of the top 5 smartest people I’ve ever known; not “players,” but people.

JK: Over the course of your career, basketball has taken you around the world and back. You played on six different continents in countries like Italy, New Zealand, Mexico, France and Greece. Having been born and raised in the United States, did you have any trepidation about playing overseas? Also, being deaf and having to communicate with coaches/teammates who spoke broken English – how difficult did this make your international experience?

LA: This is a good question. There have been a lot of jobs that I lost, even after I signed the contract, once the coach found out that I had hearing loss. But the funny thing is that even though I played without my hearing aids, I tended to use my lack of hearing as my strength; as an advantage because I had to rely so much more on being a visual player and approaching basketball like a game of chess. In the fourth quarter – in a loud arena – everyone in deaf. My famous saying is, “In the land of temporary deafness, the permanently deaf man is King.”

I always knew I was playing for a coach who didn’t know his offense if he was too insecure to use hand signals during the game. You have to use hand signals in the fourth quarter anyways – it’s so loud. Also, because no matter what offense you run the defense always has to give you something. So if you are afraid of the other team knowing your plays, it must not be a very good offense. I never really had much of an issue with the broken English overseas. It was a problem from time to time, but, for the most part, I understood people’s body language, so I could usually always keep myself abreast of what was happening.

JK: In a previous interview with the Salt Lake Tribune, you said, “Every European locker room I’ve ever been in doesn’t even live up to my college locker rooms. There are grease-stained floors, cockroaches, shower heads that don’t work.” You also claimed that you once signed a contract for $160,000 to play for NSB Napoli in Italy “didn’t receive a dime of it.” What advice would you give an American born player who is thinking about taking his career into foreign territory?

LA: I would tell any player that wants to go play overseas, or any parent that wants their kid to play professional basketball, this truth:

I would never wish this life on my son. It’s a very lonely life. You sacrifice a lot of relationships, friendships and intimacy chasing the game, thinking you will find your validation and a big pay day there. You’re also led to believe that, aside from basketball, you have no other skills to offer the world. As a result, you live out of suitcases hoping to make enough money to buy yourself time to figure out how you’re going to transition out of the game. People need to realize that signing a contract overseas – as a player from the United States – doesn’t mean anything. It’s just a piece of paper, so you’re basically on a constant trial basis wherever you go. You also have to realize that you’re practicing twice a day, five days a week, for ten months in the European Leagues. You play one game every week; that’s four games per month. So if you have two bad games in a row that means that you had a bad month and you’ll probably lose your job.

There’s a very few things that are sexy or friendly about playing overseas. You’re always living out of a suitcase. You never know if you’re going to have your job tomorrow because, even if you’re playing well, sometimes owners will find someone better. Owners are always looking for someone bigger, better and faster. They always think that “Phantom” player is out there somewhere. Now with YouTube, there are so many aggressive agents that are given the ability to easily make any player look like an All-Star. With enough editing, any player can look All-World. Owners and general managers who don’t really know basketball will watch someone’s highlights on YouTube and say, “Wow, this guy is amazing, every basket is a dunk! Bring him in.”

It’s a nasty business. I tell people to pursue it if you want, but to be prepared for a very crazy ride where very few things are within your control. You can be the best player on the team, but if your Serbian coach is insane and doesn’t like you, it doesn’t matter.

JK: Since retiring from professional basketball, you’ve founded L Squared Productions and have achieved a great deal of success as a keynote motivational speaker. Talk about some of the initiatives your company is working on, especially, pertaining to your public speeches.

LA: As I retired and transitioned into keynote speaking, my original model was speaking to corporate and nonprofit settings to get the funds to then speak to at-risk youth. I realized, though, that I needed a “game-changer” and I found it by partnering with some friends in the tech world to create Manestream.

Manestream is a full-service online education platform, a school in the cloud for any child, where they’ll have their own laptops, the fastest network and our powerful backend data centers. As a speaker, this allows me – when I travel around the country speaking at-risk youth – to empower them with access to all the education they can possibly have and to write their own scripts for their lives.

It’s incredibly exciting that I get to be a speaker that also is able to “follow through” because everyone is tired of speaker that comes and says, “Well, you guys are awesome. Okay, that’ll be $5,000. Thank you very much and you’ll never see me again, unless you want to pay 5,000 again to hear the same speech.”

Instead, I get to be a recurring mentor in their lives, whether it’s them seeing me in person or everyday on their computers through our platform. This is just touching the tip of the iceberg because once you go to the website and see all that we’re capable of it’s incredibly exciting. Our first philanthropic school, from that it looks like, will be a special needs school in Cambodia that will equip kids with their free endpoints and online access to education. It’s incredibly exciting; the world that we live in.

Image courtesy of Lance Allred/Facebook

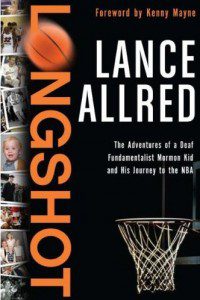

JK: You’re also the author of two critically acclaimed books: Longshot: The Adventures of a Deaf Fundamentalist Mormon Kid and His Journey to the NBA and Basketball Gods: The Transformation of the Enlightened Jock – which went #1 on Amazon in three different categories. What inspired you to become an author? And what type of receptions have you received from people who have read your book?

LA: Longshot and Basketball Gods – I am very proud of both of them. I started writing Longshot during my first year in professional basketball as a cathartic means to relieve stress. I had no intention of getting it published. Not only was writing a coping mechanism – as my parents had always encouraged me to read and write when I was a kid in speech therapy – but I also wrote it for my future kids to read, so they’d know who I was and learn vicariously from some of my lessons.

When I was called to Cleveland, HarperCollins [Publishers LLC] heard my story on NPR (National Public Radio) and they bought the manuscript shortly after. I gave them 800 pages, but they wanted it down to 250. The editing was brutal. I self-published Basketball Gods, the sequel because I just wanted more creative control over the experience and I’m glad I did that. The great thing about books is that they have so many lives. If a book doesn’t do well initially, doesn’t mean it won’t do well 5, 10, or 15 years later. Now that I do public speaking, my book sales are picking up again. It’s not so much the sales that I care about; t’s just nice knowing that people are actually reading my books. That’s the most important thing.

My advice to any aspiring writer would be: Don’t write under the pressure of having your work published. Let the book intrinsically develop as it needs to. If it’s supposed to be published, it will be published. Don’t measure your book’s worth by the outcome. Remember this: publishing is a racket. It’s a silly business. Most New York Times Best Sellers are measured on the pre-sale order because wholesale orders out of the factory. They don’t count retail sales. 50 Shades of Grey has sold however many copies in print, does it mean it’s a good book? Absolutely not.

JK: Whether as a basketball player, author or speaker, your story has inspired countless people – with and without disabilities – all over the world. Lastly, what do you want your legacy to be?

LA: The only limitations that exist in life are the ones we place on ourselves. Failing or succeeding isn’t nearly as important as whether or not you try. For all I know, this is the only life I will have. So, why wouldn’t I go and do everything I ever wanted to do? Why not? Even if I fail, it is far better than the hell that is the mediocrity of never daring to try. People see my success, but they don’t see the heartache and brutal bouts of self-doubt. But through all the blinding highs and crippling lows, I have chosen, time and time again to get up and keep playing on. Why? Because I choose to.