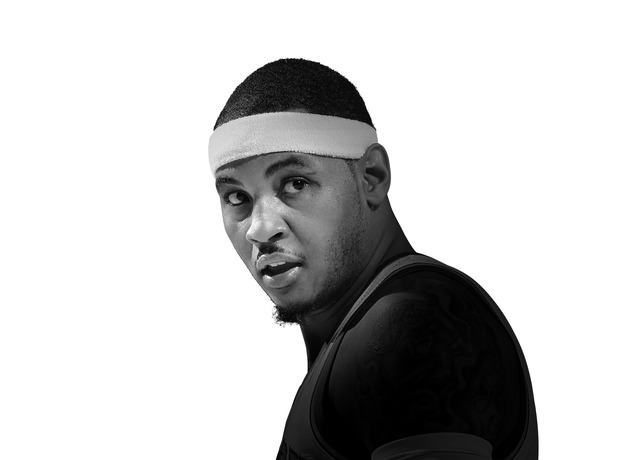

Carmelo Anthony’s career of contradictions continued in a confusing 2005-06 season. At the end of that regular season, it was reasonable to consider him the best player of his generation to that point.

The arrival of new head coach George Karl part way through the previous season invigorated the Denver Nuggets and sent them on a run into the playoffs, but it was based mostly on open play, drive-and-kick and transition offense. Karl’s scheme – or as his critics would come to say, lack thereof – seemed to work immediately in Denver, accompanied by all that talk of running people out of the gym at Denver’s altitude.

And run the Nuggets did, as well as score.

In Anthony’s third season in the NBA, the coach who most was known for free-flowing offense put one play into his playbook: The Melo Isolation.

In his first two seasons, Carmelo Anthony scored the majority of his buckets by leaking out in transition and being a tremendous finisher, or making back-cuts to the basket for lob passes from Andre Miller, or even getting garbage-point put-backs.

But in Year Three, one of the central ironies of Anthony’s career would begin to unfold, as even Karl recognized that it made absolutely no sense to not use arguably the best player ever built for elbow-isolation offensive basketball. Years later, this practice would beckon the moniker “ball-stopper.” But believe this, there is no coach in the NBA who wouldn’t have that play as part of the offense if they had Anthony.

From the triple-threat position on either elbow, Anthony is almost impossible to guard when he is on. He has both one of the quickest first-steps and releases in the NBA. This essentially creates a game of rock, paper, scissors with his defender. If he slacks off at all, wary that Anthony will use his quickness to get by him, he is giving Anthony an open look as his quick release makes a late-arriving contest moot: He’s already shot the ball.

If his jump shot is going, guarding Anthony immediately becomes a two-person job, as a help defender will be required when Anthony gets past his guy after a pump-fake or two. His ability to finish and draw contact at the basket is well-documented.

Anthony’s scoring blossomed with this new wrinkle in the system and jumped to 26.5 points per game, good for eighth in the NBA. He hit five game-winning shots in the final five seconds of games and three more in the final 22 seconds. Nearly all of these shots were on isolations.

That year, Anthony played in 80 games, shot over 50 percent on his two-point attempts and led the Nuggets to their first Division Championship since 1988. I was two years old in 1988.

By the end of the year, every time he had the ball in his hands in a clutch situation the people in colorful Colorado believed the ball would go in, and it did. His clutch numbers, according to 82games.com, put him ahead of Kobe Bryant as the most reliable late-game shot creator in the NBA. He was on fire and it was fun to watch.

But for every action there is an equal and opposite reaction.

With Marcus Camby and Nene sidelined for large chunks of the season due to injury – and having a guard unit comprised of Miller, Earl Boykins, Greg Buckner and Demarr Johnson – teams learned to load up on Anthony since the Nuggets didn’t have the shooting options to punish them for it.

Their playoff series against the Los Angeles Clippers was laughable for so many reasons.

First, it would become the reason for rule change as the Clippers (led again by an infuriatingly alien-like Sam Cassell) tanked the last few games of the season to face the Nuggets, who had the higher seed due to winning the Northwest Division, though with a worse record. The hobbled team won only 44 games that season. Therefore, the Clippers (the lower seed with the better record) had home field advantage during the NBA Playoffs.

It probably wouldn’t have mattered anyway since the Clippers practically triple-teamed Anthony any time it looked like he might get going. The rest of the team failed to shoot at all and Kenyon Martin imploded and was benched by Karl.

You don’t build legends in the regular season. Carmelo had a regular season for the record books. 0-3.

Over in the East, LeBron James finally made it to the playoffs with an impressive fourth-seed and 50 wins. Then he did something Anthony just seemed incapable of at this point: He got out of the first round.

The Cavaliers bested that ol’ powerhouse Washington Wizards team in six games. Cleveland lost in the second round to the Detroit Pistons. By beating Gilbert Arenas, James would avoid the scrutiny and the pressure that fell on both Anthony and the Nuggets in the following season for being “first-round flameouts.” People were tired of losing in the first round of the playoffs. James had just gotten there for the first time. Oh well.

In 2006-2007, the Denver Nuggets turned into a Fellini film.