All images courtesy of jerrodmustaf.com.

Jeffrey Kee: Talk about your upbringing a little bit. As a kid who had just moved to Maryland from North Carolina, how did you get the attention of [legendary DeMatha coach] Morgan Wootten?

Jerrod Mustaf: In Greenbelt [Maryland] there was this community center that everyone went to. I used to go there every day to work out. One day, a youth volunteer coach named Mike Gielen saw me play. He approached me and said, “How old are you?” When I told him I was 13 he was shocked. He talked to my dad about my potential and I ended up attending the DeMatha Basketball Camp, which at the time was called the Metropolitan Area Basketball School. I actually had gone to the camp the summer before, when I was 12, but I was awful. That next year, I came back and was dunking on people – I was a totally different player. I ended up outplaying everyone at the camp and won MVP honors. Morgan Wootten noticed that. He called me into his office and talked with my dad and I about playing for DeMatha. Not too long after that I ended up enrolling. Interestingly enough, I got my first recruiting letter from [former Georgia Tech head coach] Bobby Cremmins that summer. He saw me play at the camp. I was about 6’5 – back then there weren’t many 6’5 eighth graders.

JK: As a freshman at DeMatha, you were teammates with Danny Ferry, right?

JM: Yes, I was. I was 14 at the time. Danny was an awesome player. As a matter of fact, some days, he used to give me rides home from practice. He would kick my butt in practice, then give me a ride home and trash talk me the whole time. Danny was a character, man. The thing I appreciated most about playing against the No. 1 high school player in the country, as a freshman, is that playing against him every day in practice made the actual games much easier for me. I was just a great experience playing against Danny. He was a very smart, savvy player, and he made me a better player as well.

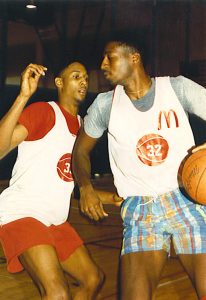

JK: Your senior year, you were selected – alongside guys like Shawn Kemp, Alonzo Mourning and Christian Laettner – as a 1988 McDonald’s All-American. What was that experience like?

JK: Your senior year, you were selected – alongside guys like Shawn Kemp, Alonzo Mourning and Christian Laettner – as a 1988 McDonald’s All-American. What was that experience like?

JM: Being selected to play in the McDonald’s game was a huge honor. From what I’ve seen, that 88’ class was one of the better classes in high school basketball. By playing at DeMatha, I was always competing against the best players in the nation, so I already had a lot of firsthand experience playing against these guys. I remember playing against Hank Gathers as a freshman. Hank and Bo Kimble played over at Dobbins Tech [Pennsylvania]. I played against Sherman Douglas. I knew Billy Owens as a freshman – he was a 6’3 in his first year of high school. I watched Shawn Kemp. I played Alonzo Mourning in AAU. I also played in the Nike Camp, so I had already played against a lot of the top guys in my class. Collectively, we were a strong, strong group of players.

JK: You and Alonzo Mourning were two local guys – you being from Maryland and Mourning hailing from Virginia. Were you two friends at all?

JM: I wouldn’t say “friends.” We knew each other on a friendly basis and we respected each other, but we were competitors in high school. I first saw his name when I was in the 9th grade. We played each other a few times in AAU basketball. I followed his career. I knew who he was. He knew who I was. But being a University of Maryland guy and with him going to Georgetown, we didn’t hang out; we didn’t socialize. We were kind of like cross town rivals.

JK: Your college recruitment process was very unorthodox. Coaches who were interested in recruiting you were forced to fill out a questionnaire that your family devised – questions included topics regarding the number of black faculty members on the university staff to the percentage of black students and athletes graduated to the number of blacks on the athletic staff. Who came up with that idea?

JM: That was my dad’s idea. He was a very conscious parent. He was conscious of a lot of things that were going on socially. He felt that my recruitment was an opportunity to make a difference. He talked it over with people who were respected in the community and together we devised the questionnaire. Most importantly, it was about making people aware about something that had not been done before and got people to ask themselves, “Why not?” Looking back, I feel that we did that with the questionnaire.

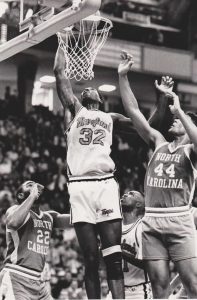

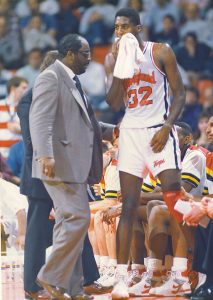

JK: What convinced you to play for the University of Maryland?

JK: What convinced you to play for the University of Maryland?

JM: A lot went into it. I had the opportunity to meet with John Slaughter. He was the first black Chancellor in the ACC. Bob Wade was the head coach at the time. He was the first black coach in the ACC. We talked about a lot of things. We talked about how the team would utilize my skillset once I got to college. We talked about having a section for underprivileged kids, so that they could attend games and see college athletes up close. But a lot of the things that we discussed never had the opportunity to play out because John Slaughter was fired before my freshman year. Brian Williams, our starting center, transferred to Arizona. So a lot changed from the time I initially began considering Maryland. At the same time, Maryland was in the ACC. We were going to play a lot of the Tobacco Road teams. Being from North Carolina, my family would have a chance to come watch me play. Our games were going to be televised as well. So when you look at the overall package, Maryland stood out the most; more so than any other school. They were offering a lot of what I was looking for, which is why; ultimately, my decision to play there was a no-brainer.

JK: When you said Brian Williams – do you mean [former NBA player] Bison Dele?

JM: Yep, he played for Maryland a year before I arrived. He would have been the starting center my freshman year.

JK: Why’d he transfer?

JM: I don’t know for sure. Brian was a West Coast guy. He was originally from Santa Monica. He would be walking around the University of Maryland wearing flip flips in the winter and shorts in the snow. He was a just different kind of guy. He ended up transferring to Arizona and played alongside two other centers – one of them was [former NBA player] Sean Rooks. I thought he would have made a bigger impact if he had stayed in the ACC, but for whatever reason, he decided to transfer and it worked out well for him.

JK: But being a big man, didn’t him transferring benefit you?

JM: No, I was going to start my freshman year anyways. Remember, I was a three time All-American in high school, so I was going to start. Also, I wasn’t a center. He played center. I was a hybrid player – I played both the small forward and power forward positions. I could go inside and outside. At Maryland, I was going to be a post-up, small forward, sort of like the way Danny Ferry was at Duke. If Brian Williams would have stayed – having him and Tony Massenburg would have allowed me to do that.

JK: You got a chance to play Danny Ferry twice during your freshman year. What was that like?

JM: Oh, I was looking forward to it. I was excited about it. I couldn’t wait to play him. I scored 16 the first game and 18 in the second. As a freshman, I averaged 18 points against the ACC, so I was no slouch.

JK: After posting 19 points and eight rebounds per game as a sophomore, you decided to forgo your final two years of eligibility and declare for the NBA draft. I read, though, that you left Maryland, not necessarily because of the NBA, but because of your disdain for the NCAA. Talk about that a little bit.

JM: The bottom line is that I’ve always had a problem with the NCAA. I couldn’t have seen myself continuing to play within that system. They’re completely unfair to the players. They always have been. They oppressed us. I remember Nike gave our team sweat suits. Everybody that I knew in college sports had these sweat suits. The NCAA made us give them back. They said we couldn’t accept any perks, but it wasn’t a perk. There were just so many things of that nature that I thought were so ridiculous that it made me not want to be in that type of system anymore. One of the reasons why I went to Maryland is because we played on television – my family could watch me play. The NCAA banned us from playing on TV. I didn’t do anything wrong. My teammates didn’t commit any violations or break any rules. We, the players, were unfairly punished. That made me not want to be a part of the NCAA any longer. After my sophomore year, there was an opportunity for me to play in the NBA, and I ended up taking that route.

JK: The sanctions that the NCAA handed down because Coach Wade had one of his players driven to class, right?

JK: The sanctions that the NCAA handed down because Coach Wade had one of his players driven to class, right?

JM: That’s right and it’s the most ridiculous thing I’ve ever heard. I understood what had happened and was in complete support of Coach Wade. In my estimation, a coach assumes the role of a father figure, as a mentor and as a role model. A lot of times, players sign to play for certain schools because the coach will go into the student athlete’s home and convince them that they’ll take care of them as if they were their own child. Coach Wade did that. He went to Baltimore and picked out Rudy Archer and gave him an opportunity to succeed in life. Coming from the inner city, Rudy didn’t have the necessary tools that other kids had to succeed in the classroom. Coach Wade found a way to enroll him at Prince George’s Community College and had one of his assistants drive Rudy back and forth because he had no other means of transportation. That is what a coach is supposed to do, and for him to lose his job and lose everything because of that was completely unfair. I wish more coaches cared for their players the way Coach Wade did.

JK: Sanctions aside, ultimately, you were selected 17th overall by the Knicks in the 1990 draft. Describe your rookie season in New York.

JM: I really enjoyed it. Being the youngest player in the league – it was a great learning experience for me. As a rookie, I played three different positions – small forward, power forward and center – which is very tough to do. And I’d say I did pretty well because over the course of the season, I earned Player of the Game honors at all three positions.

JK: What was it like being teammates with guys like Patrick Ewing and Charles Oakley?

JM: It was great. I learned a lot from those guys, so I really valued the opportunity to compete against them every day in practice. Oakley and I enjoyed a great relationship off the court, even though I was drafted to eventually challenge him for his position. He taught me a lot about the NBA, both on the court and off.

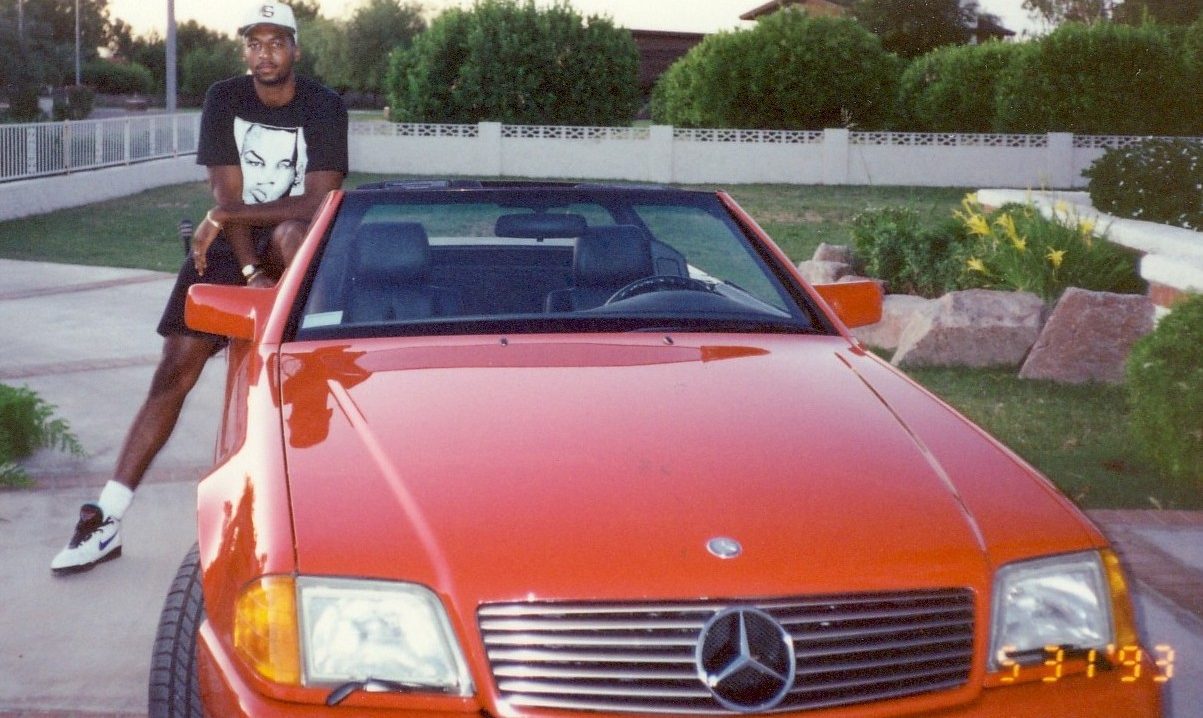

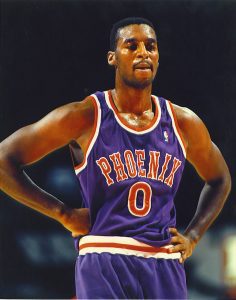

JK: After your rookie season, you were traded to the Phoenix Suns in 91’. Talk about the differences in culture between the Knicks and the Suns.

JK: After your rookie season, you were traded to the Phoenix Suns in 91’. Talk about the differences in culture between the Knicks and the Suns.

JM: When I got traded to the Suns, it was a complete culture shock. I had never been to Phoenix before in my life. It was 105 degrees the first day I got there. It was October, too. I was like, “What is this?” Back in 2005, the NBA implemented a league wide dress code. Well, with the Knicks, we had a team dress code. Everyone on the Knicks wore suits. When I first got drafted, the guys on the team introduced me to their custom tailor, so I ended up getting a bunch of suits made that I would wear to the games. It was New York City, so we had to dress a certain way. In Phoenix, though, the culture was completely different. I arrived in a suit for my first game with the Suns and was the only player with a suit on. The other guys were looking at me like, “What are you doing?” They were wearing flip flops, t-shirts and polo’s to games.

JK: Was that because of the hot Arizona weather or was the team dynamic just a lot more relaxed?

JM: It was both. On the West Coast, everything is much more laid back. Tom Chambers wore cowboy boots and cowboy hats. Dressing up to them was throwing on a polo shirt. It’s just a completely different environment. When I was on the Knicks, on our team bus, all the black guys would be in the back gambling and playing cards – Ewing, Oakley and Mark Jackson. On the Suns, Chambers, Ed Nealy and Jeff Hornacek were in the back of the bus. I was like, “What are ya’ll doing in the back here?” Everything was completely reversed.

JK: Not naming anyone in particular; what’s the biggest hand you’ve seen someone lose?

JM: The biggest loss I’ve seen was $13,000, but to these players, that’s nothing.

JK: Talk about the spending culture in the league. When you were earning NBA paychecks, were you living lavishly as well?

JM: Of course because in the NBA there is a certain standard of living that you have to live up to. Obviously, when you’re making a lot of money like that, naturally, you want to live in a better environment. There are a lot of expectations to live a certain way. There’s competition as well. Whether it’s about who owns the latest BMW, Mercedes, or Porsche. Guys compete over that type pf stuff all the time. Everybody wants to have something before everyone else. They want the phone that isn’t coming out until next year. They want the shoes that won’t be released for another six months. Everything in the NBA is a competition.

JK: Around that same time, at the age of 22, you started your own corporation – Jerrod Mustaf Enterprises – which focused on a plethora of things like computers, music, real estate, fashion and a bookstore. Despite making millions in the NBA, what influenced you into starting your own company at such a young age?

JM: It was always something that I wanted to do because I was never satisfied being just a jock. I had very diversified interests and NBA owners weren’t always happy about that. Management wants you to be singularly focused on strictly basketball. Some people are and a lot of them end up doing extremely well, but I was not one of those guys. I’ve always enjoyed other things aside from basketball. I was always trying to find my purpose in life and the corporation was something that was very important to me. It’s actually one of the things that Jerry Colangelo and I bumped heads about. He wanted to know why I was selling t-shirts and working on my bookstore instead of focusing on basketball. But I understood where he was coming from. As a team owner, you’re paying your players millions of dollars, so you want them to focus on being the best player they can possibly be. I understood that. For me, I knew that basketball wasn’t going to satisfy me for the rest of my life, so I focused on my outside interests too. I didn’t think that it took away from my basketball career, but that was something that Jerry and I were in disagreement over. I thought it was unfair, though, because Dan Majerle had a sports bar that was heavily supported by the Suns. I had a bookstore in a black community that needed one, but I never received any support for it. That’s because Dan Majerle was a proven commodity. When you’re a top player like that, you can do things of that nature.

JK: In 93’, you were involved in the infamous Kevin Johnson/Doc Rivers brawl that resulted in $160,000 worth of fines. What do you remember most about that fight?

JM: Besides being fined, I remember getting injured. During the fight, I pulled my hamstring trying to get people off of Kevin Johnson. After the initial fight happened between him and Doc Rivers, Kevin and Greg Anthony started fighting. I see Pat Riley grabbing Greg Anthony, trying to hold him back. I didn’t know what was going on, so I ran over there and was tried to help pull people away from Kevin. My adrenaline was rushing so fast that I didn’t even realize until the second half that I had pulled my quad – it had locked up on me and I wasn’t able to go back out on the court. So I remember that. Plus, I got fined like $12,000.

JK: What did the league fine you for?

JK: What did the league fine you for?

JM: I told them I was trying to break the fight up, but the league didn’t see it that way. The great thing about [former Suns owner] Jerry Colangelo is that he paid the fine for me. I’ll give him credit for that. He understood my thought process. Kevin Johnson was one of our star players. If our organization wanted to win, we needed Kevin out there on the court. As his teammate, it was my job to try and protect him, so I went out there and made sure he was okay. Jerry liked that and respected what I did.

JK: But as a player, you didn’t really like Jerry Colangelo, right?

JM: I didn’t necessarily like him, but I appreciated him. Jerry could have been a spiteful owner and he wasn’t. I understand business, and when I was a player, I didn’t really understand the business aspect of the NBA – in terms of contracts, players getting traded or cut – like I do now. Looking back on it, I have a better picture of who Jerry actually is as a person as opposed to when I was 23 because I understand that certain decisions he made weren’t personal; it was just business.

JK: Later that season, your Suns matched up against Michael Jordan and the Chicago Bulls in the 93’ NBA Finals. What do you remember most about that series?

JM: I remember having a whole entire week to hang out in Chicago. The Bulls fans were amazing; they were crazy! I remember telling myself, “Man, this is history.” It was Michael Jordan versus Charles Barkley. I remember the triple overtime game [Game 3]. I remember people in Chicago boarding up their buildings and windows because they were expecting a riot if the Bulls had closed us out in Game 5 – but we ended up winning that game and going back to Phoenix thinking that we had a chance to win Game 6 and 7 at home for the championship. We were so close to forcing a Game 7 and we would have if John Paxson wouldn’t have hit the game winning three-pointer [in Game 6]. Even so, it was a very exciting time and it was a great experience to be a part of the NBA Finals. It was an honor to be a part of a team that had won as many games as we did.

JK: Describe what it’s like being on the losing end of an NBA Finals run.

JM: You’re sad. You’re dejected. But we played our hardest and knew that we had given it our best shot. Also, when you lose to Michael Jordan, you just have to accept the fact that it’s Michael Jordan, so it’s kind of expected. When you look back on his Finals record, he never lost.

JK: After three seasons in Phoenix, you packed your bags and headed overseas to Europe where you won championships in Spain and in Poland. What was the international experience like for you?

JM: It was different, but it was a great experience that opened my eyes up to the world. In America, we’re boxed in; we don’t think of anything outside of our borders. Being exposed to the world opens your eyes up to everything. I really enjoyed that. Looking back, I wish I had spent more time sightseeing and meeting new people, but one of the big differences between the NBA and playing overseas is that you don’t really have as much time to yourself as you would like. In Europe, you practice twice a day. If you play for a good team, you’ll travel throughout Europe; you don’t just stay in one country. I had a chance to travel to places like Germany and Austria. I went to Jerusalem, which was amazing to me because I grew up reading the Bible. I had the opportunity to see how different people lived, shopped, partied and enjoyed life. These were really once in a lifetime opportunities. I got to see a whole different side of the world. It was just a great experience.

JK: The best part is that the team pays for everything, right?

JM: That’s right. The team pays for everything. Basketball has really blessed me with a better quality of life. I’m always grateful because I’ve had the opportunity to do things that most people couldn’t even imagine doing. When I talk to people and they wonder why I think the way I do; it’s because I’ve been exposed to so much. I’m really blessed to have had the opportunity to experience all of that.

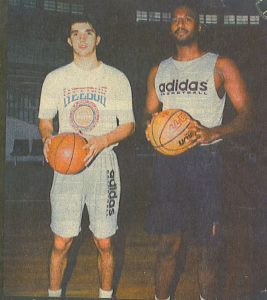

JK: On your website, I saw a picture of you standing next to a young Peja Stojakovic. Were you two teammates at one point?

JK: On your website, I saw a picture of you standing next to a young Peja Stojakovic. Were you two teammates at one point?

JM: Yes, we were teammates in Greece. Peja had just come from Yugoslavia and he was trying to become a Greek national. He was 16 at the time, and I had never seen a 16 year old kid as talented as he was. His practice routine was phenomenal. His shooting ability, at that age, was unbelievable. He was just such a talented player.

JK: At that age, was Peja strictly a shooter or had he already developed a complete game?

JM: He was solid, in terms of size, but he could shoot so well. He was always shooting- before practice and after practicing – trying to prefect his jump shot.

JK: How do you think he would have fared in the three-point contest against Steph Curry?

JM: Well, I think Steph Curry is on a whole different level. At the time, though, I had never seen someone so young who would just come out onto the court and shoot the ball the way Peja did. It’s different for grown men, but even at 16, he had the laser focus and the hunger to be a great player. I also played with Juan Carlos Navarro when he was 16. When I played in Barcelona, he was on our junior team, but he was called up to play for us when a couple of our guys got injured. That kid was so fast. I knew then that he was going to be a very good player. Now he’s one of the best players in Spain. Pau Gasol was on our junior team too, although, I never thought that he’d turn into the type of player that became.

JK: Why is that?

JM: I’ve seen a lot of tall and lanky kids in my lifetime. Europe is full of them. The biggest kids that I’ve ever seen were in Poland. Poland and Russian produce thick seven- footers; a lot of them. So I never thought Pau would materialize because there were so many players just like him.

JK: After retiring in 2001, you founded the Street Basketball Association (SBA). What inspired you to start your own league?

JK: I had just finished playing in Poland and a buddy of mine convinced me to spend some time with him in Turkey. He told me it was like Hollywood out there – that it was just like Los Angeles. I went out there for about a month. We were in Izmir, Turkey on the beach and they had basketball courts lined up one after another. I said to myself, “Wow.” Basketball is literally all over the world. We were in Turkey and they had all of these basketball courts. I had interned at the NBA office in the summer while I was a player because I had an ambition of being on the business side one day. My eyes were opened to the endless opportunities to make a living through the sport of basketball. I remember thinking to myself, well; back home [in D.C.] we have all of these local legends who didn’t make it to the NBA. I wanted to bring all of them together, put them on a team and travel around the world competing against the best players. So, I formed the Street Basketball Association. The NBA ownership was limited to the ‘good ole boy’ network and the NCAA operated like a modern day plantation system. Therefore, grassroots basketball development and street basketball were the only options available to a basketball entrepreneur like myself.

JK: Okay, so the SBA was composed of the best of the best from each city?

JM: Exactly. The SBA is kind of like an AAU league for adults. It’s the best players from each city that did not make it to the NBA – players who are still competing, still at the top of their game and are looking for an opportunity.

JK: Who were some of the players on the Washington D.C. team?

JK: Curt Smith was one of our stars. Greg Jones, who played at West Virginia and in the D-League for a little bit, was on the team. Guys like [Former Georgetown Hoya] Victor Page who led the Big East in scoring and Hugh “Baby Shaq” Jones from the And-1 Mixtape Tour played as well. Randy “White Chocolate” Gill – I had recruited him right out of Bowie State. Pat the Roc – I got him on the team when he was 19. He had never flown on an airplane before that. I handpicked these guys and made them part of the team.

JK: Did anyone from the NBA ever play in the SBA?

JK: Did anyone from the NBA ever play in the SBA?

JM: We had a quite few NBA guys play in games here and there, but not consistently. Jerome “Junk Yard Dog” Williams played. Muggsy Bogues, Dale Ellis, Tracy Murray, Chris Wilcox and Tim Hardaway did as well. Dennis Rodman played a few games. We probably had around 15-20 NBA guys play for us over the years.

JK: Talk about the work you’re doing with the Take Charge Program. JM: I’m the Executive Director of the program that was originally founded by my father. The mission of the program is to transform the lives of our youth – to put them back on the right track. Too many young people come to us without the proper tools to succeed in life. Our job is to give them those tools. There are so many negative things going on in their communities whether it’s drug activity or violence. We want to help steer these kids on the right path, so that they’ll have the strength and resiliency to resist the criminal activity that’s around them. That’s what the program is all about – educating our youth and giving them the tools to resist. We can’t be their parents and we cannot take them out of their environments, but we can teach our youth how to fight negativity and help steer them on a path that will help them reach their goals.

JK: What’s the program’s success rate?

JM: About 90% of the kids who complete our program do not re-offend. That’s something that we’re very proud of.

JK: Do a lot of these kids have hoop dreams similar to the one you had as a youth?

JM: If you go to any school or any program of ours and ask them what their dream is – the majority of them will say that they want to play in either the NBA or the NFL. Have they put much thought into it? No. Are they working hard to get there? No. It’s the culture that we live in. These kids see these ball players on TV and want to emulate their lifestyles. That’s all they see. But do they understand all of the work that goes into it? They don’t.

JK: As their mentor, what do you tell them when they say their dream is to be a professional athlete?

JM: Well, if somebody has a dream, I’m not the person who will tell them that they can’t do it. I’ll tell them that if being in the NBA is what they really want to do – because I’ve played in the league – I can show them how to get there. That’s if they have the talent to do so. I can teach them and walk them through the steps that they have to take in order to make it to that level. Before basketball, though, they must have their priorities straight – God, family, education, and then maybe basketball. I tell them not to let anything get in the way of those priorities. If they can keep those in order, then maybe they’ll have a chance because that’s the foundation to success. I’ve seen so many unbelievably talented guys not make it to the NBA because they didn’t have that foundation. The missing ingredient is always discipline.