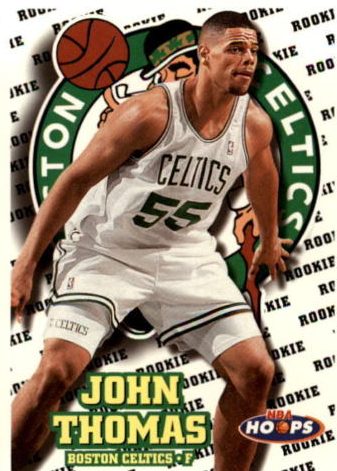

Image courtesy of John Thomas/Instagram.

Jeffrey Kee: Talk about your upbringing a little bit. Did you come from a basketball environment?

John Thomas: To some extent I did. My father played professionally overseas, but he never pushed me to play. I had dabbled in basketball in junior high, but I always ended up quitting. I never really found a passion for it. It wasn’t until I was 15 years old when I really starting taking a liking to the game. It was mainly because my peers really encouraged me to get out there and play. I wasn’t very good, but they kept saying “John, it doesn’t matter. You’re big.” At the time, I was about 6’7. The running joke amongst my friends was that I couldn’t run and chew gum at the same time. I couldn’t dunk. I was one of those players that had a lot of insecurities. I was always concerned with how big my opponents were and things like that.

Where I grew up, in the inner city of Minneapolis, I started practicing my skills at the local community center. I told them I wanted to use their gym and in exchange, I would sweep their floors. I worked on my handles, practiced my shot and played 21. I played against a lot of adults and against them is where I honed my skills. When the gym closed and the lights went off, I would go outside and continue to play. Even still, I wasn’t great. People told me all the time that I didn’t have what it took to play at the next level, but ultimately I was able to use that as motivation. The more I worked, the more I would fall in love with the game.

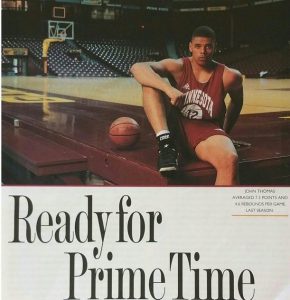

JK: After starring at Roosevelt High School (Minneapolis, MN) you signed on to play for Coach Clem Haskins and the Minnesota Gophers. When you first arrived at the University of Minnesota in 1993, were you thinking about the NBA at all?

JT: The NBA was the furthest thing from my mind because, at the time, I felt like I had so much catching up to do. There were so many other players that were more skilled than I was. I was very unsure of who I was, what type of player I was and who I wanted to be. I also didn’t have 100 percent backing from my high school head coach. In a meeting with my father, my coach mentioned that he believed I’d never become a great player, but then again that was just more motivation for me. Because of this, I never thought about the NBA. I just took things step by step. I was always known as that blue collared worker; someone who was going to do all of the dirty work. Even though I had been blessed with a 6’9 frame, I knew that I had a lot of work to do before I could even start thinking about the NBA.

Image courtesy of John Thomas/Instagram.

JK: As a senior in 97’, you helped lead the Golden Gophers to their first Final Four appearance in school history. What do you remember most from that famed tournament run?

JT: I just remember how close we were as a team and how tough we were. We were playing in the Big Ten. We had a very physical team with a huge front line that would battle the entire game. I also remember how resolute we were. I can’t tell you how many close games we played; so many times we were down and had to fight our way back. We had fans on the edge of their seats throughout the entire tournament. It was just one huge thrill ride to be a part of.

JK: What was the reception like from the fans when you got back to campus?

JT: It was absolutely unbelievable; definitely one of the most memorable experiences of my life because of the sincere love and adulation the fans had for us. Playing in “The Barn” [Williams Arena] is unlike any other arena that I’ve ever played in. I’ve played in Staples Center in front of movie stars and at Madison Square Garden in New York, but there’s nothing like “The Barn.” Even our preseason games were always sold out. Mobs and mobs of people followed us on our tournament run to the Final Four. When we landed at the airport, buses of people were there waiting for us. As players, we put in so much effort and soul to get to the Final Four, so the fan support was something we really appreciated. They helped make it one of the most unforgettable experiences of my life.

JK: Looking back, would you say the Final Four run was the best moment of your career?

JT: It’s tough to say because I’ve experienced so much since then. It’s definitely up there; certainly top 5. I’ve had so many memorable experiences, both positive and negative, that have been character defining moments. Looking back on my career, I reflect on a lot on the tough experiences as well, and how they built my character. Those tough moments are actually more memorable to me because the adversity I went through made me so much stronger.

JK: I read that after your senior year, you didn’t even know if you’d get drafted, let alone be selected in the first round. When did you realize you were NBA material?

JT: That’s right. Up until then I had no idea I was good enough to play in the NBA. It wasn’t until my senior year, after we had lost to Kentucky in the Final Four; Coach Haskins told me that it was time for me to go make some money and be a pro now. That’s the first time I really started thinking about the NBA. I realized that I needed to develop a better touch around the basket and needed to improve my midrange jumper. I think I went and worked out for 18 different teams, so physically, I had to get in better shape. My mindset at the time was to work my ass off and whatever happens, happens.

Image courtesy of Celtics Life.

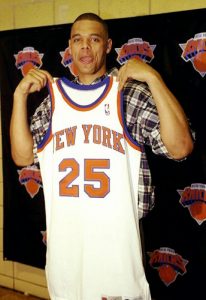

JK: You wound up being selected 25th overall by the New York Knicks; a team that had won 57 games the previous year. Ultimately, though, you were traded to the Celtics before ever playing a game for them. What was it like being traded so early into your career?

JT: I’m a very loyal person. The relationships that I keep are something that really defines me. I had put my heart, my soul and all of my energy into being a New York Knick. I was proud to be one. I felt like it was a great situation for me because there wasn’t any pressure. [Assistant coaches] Brendan Malone and Tom Thibodeau worked me to the bone every day and I loved every moment. I’ve always been someone who’s worked my tail off. When I got traded, that was my rude awakening to the fact that the NBA isn’t about loyalty or allegiance; the NBA is a business and you can literally be traded or cut at any time. I was told that I had 72 hours to pack my belongings and move to Boston. At the time, I was thinking about buying a house in New York. I had started gelling with my coaches. As a player, I began finding my footing on the court. I thought that being a first-round pick, I had the stability not to worry about being traded, but, ultimately, it didn’t matter. The Knicks saw me as a piece in a trade that would benefit their organization, so that’s what ended up happening.

JK: Did you have any idea that you were on the trading block?

JT: I had no idea whatsoever which is why the trade was so shocking to me. I pulled my groin towards the end of training camp, but I’m not sure if that made a difference. I think I would have gotten traded regardless. Jeff Van Gundy came to my hotel room, knocked on the door and asked if he could talk to me for a minute. I thought he was going to talk to me about my performance or maybe my injury. Those were the initial thoughts that came to my mind. Instead, he asked me to sit down and turn the TV off, then told me that I had been traded to the Celtics. But I have always respected Jeff for how he handled the situation; he was very professional about it. Obviously, he’s a great commentator. Jeff’s a guy who I really hope gets back into the coaching ranks. The NBA needs more leaders like him.

JK: So after Van Gundy gave you the news, what happened next?

JT: Ironically, when I got traded from New York to Boston, we were actually playing the Celtics for our last preseason game, so all I had to do was switch locker rooms. I was in my hotel, and the Knicks told me that someone from the Celtics staff was coming to get me. They came to get me before the game and took me to the Celtics locker room. Mentally, I was in a fog because everything had happened so fast.

Image courtesy of Mercado Libre.

JK: In your short tenure with the Knicks, what do you cherish most from that period of time in your career?

JT: The veteran presence on that team is something that I’ll never forget. Patrick Ewing took me under his wing and dubbed me as “his rookie.” During training camp, I remember walking the streets of Charleston, South Carolina with him as he and I talked about various things; our careers and life. Patrick was a really humble, down to earth kind of guy. Then there was Charles Oakley who was like the father figure on the team; Buck Williams and Larry Johnson. Larry was one of my favorites. I remember one time, I was walking down the hall to get my physical and he yells out, “Big fella! What’s up man?” and gave me this giant bear hug. He told me congratulations, welcomed me to the team and said he couldn’t wait to work with me. As a rookie, all of this was brand new to me. I didn’t know what to expect from the league, so having these guys around was huge for me.

JK: A lot of times, in the NBA, off the court mentorship is just as important as it is on the court. Aside from helping you become a better basketball player, how did these guys impact you off the hardwood?

JT: Certain guys provided me with the ins and outs of what it took to be a professional. Patrick Ewing would tell me stories about his life, what to expect in training camp and what he did to prepare himself before games. There is so much more I wish I could have asked before I got traded; like how to take care of your money and how to deal with not playing as a rookie. Overall, I’ll say that I had good relationships, but not true mentorship. Mentorship requires the mentor to understand that the mentee has no clue due to lack of experience. In the NBA, incoming players are at a complete disadvantage if they don’t have veteran teammates looking out for their best interest. Family, friends, agents and team staff try to help, but only the NBA vet has the proper context to give the right advice. I always longed for a “big brother” to look out for me and show me the ropes because I really didn’t understand what it took to be successful in the NBA.

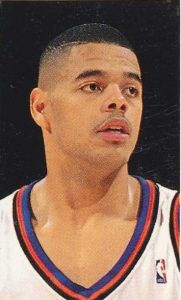

JK: As opposed to the Knicks, the Celtics were actually a relatively young team. You, Chauncey Billups and Ron Mercer were all rookies. Antoine Walker was in his second year. Coach Rick Pitino had just returned to the NBA. What was that experience like?

JT: Playing for the Celtics was a huge adjustment. Our very first game of the season was nationally televised on TNT against the Chicago Bulls. Coach Pitino sent me into the game. I’m out there on the court with Michael Jordan, Scottie Pippen and Dennis Rodman. The Bulls had just won the championship the previous year, so they were really, really good. On one play, I blocked Jordan’s shot, which sent me into this daze where I couldn’t even focus. Just a few years before that I was playing with Jordan in a video game, so blocking his shot was so surreal. Because I was so excited, I got tired quickly. Coach Pitino pulled me out of the game and called over to Shaun Brown [the Celtics strength and conditioning coach] and said, “I need 20 pounds off of John Thomas by tomorrow.”

Remember, I was a very physical player, who loved to pound under the rim; sort of like a Charles Oakley. Being a former college coach, Pitino loved to press in the backcourt, so playing for the Celtics was a very defining moment in my career because Pitino wanted to transform me into this skinny guy. I was forced to run on the treadmill before and after practices to burn weight. Because of that, my time in Boston, outside of the relationships I formed with the players, wasn’t a very enjoyable one. When I got traded to Toronto, I was thankful because Coach Butch Carter understood the type of player I was and put me in a position where I was able to flourish.

JK: It seemed like Pitino wanted to convert you into one of these modern day, speedy big guys. You said he wanted you to shed 20 pounds. Did you lose the weight?

JT: No, I didn’t. I had always played at around 260-265 pounds. I might have trimmed a little extra body weight, but nothing too drastic. I wasn’t out of shape. I had just left college and had to just get used to playing at the NBA pace. The thing Coach Pitino didn’t take into account was that I had just recovered from a groin injury. Coming off of the injury, of course, I wasn’t going to be in tip top shape. Also, I was just young and excited to be playing against THE BULLS. Nerves were getting the best of me, not my conditioning.

Image courtesy of eBay.

JK: Going back to you blocking Michael Jordan’s shot. Did you trash talk him afterwards?

JT: No way! Too much respect for him to do that. I was guarding him off of a switch from a pick and roll. He made a move, I blocked him and from there my mind went blank because I was so excited.

JK: Four months after you were traded to the Celtics, you, Chauncey Billups and Dee Brown were sent off to an even younger Toronto Raptors team. Record wise, the team struggled, but you had arguably your best seasons in Toronto. What do you remember most from your three seasons as a Raptor?

JT: First and foremost, playing in Toronto was awesome. It’s like a clearer version of New York. It’s full of culture. It’s full of so many different types of people. Fans were so welcoming. Overall, playing for the Raptors was a great experience for me. In my second year in Toronto, I really started to find my stride in the league and began playing really well. I started 10-12 games, we went on a long winning streak and I felt very comfortable within the offense. It was a time where I thought my career was really heading in the right direction.

JK: What was it like playing with Vince Carter and Tracy McGrady?

JT: Vince and Tracy are both amazing and funny guys. People ask me all the time if I saw highlight dunks in practice. I did sometimes, but not as often as you’d think because Charles Oakley wasn’t having any of that; he wasn’t going to let anyone dunk on him. It was just so much fun being on that team because Vince and Tracy were on the verge of becoming superstars. I used to clown them in the locker room. “T-Mac” wore braces and used to put wax on them, so I used to take his leftover wax and put them on my teeth, mimicking him. It was just a lot of fun being around those guys.

JK: You mentioned that in Toronto, Coach Butch Carter understood your game and was able to use your skills most effectively. You also talked about your respect for Jeff Van Gundy. Which of the two was your favorite to play for?

JT: In a short period of time Van Gundy was, but over the course of my career, my favorite was Butch Carter because I was able to play for him the longest and we were able to establish a very strong relationship. Butch was a player’s coach. He was very smart and understood all of the little details that went into basketball. As a young player, he was able to get the most out of most out of me. I don’t think I was as mentally prepared as I needed to be in order to deal with the NBA because it’s a fast moving business. I needed someone who really understood the game and would take the time to explain not only the ups and downs of playing in the league, but also the daily grind and preparation needed in order to succeed.

JK: In your second season in Toronto, Vince Carter was one of the team’s three rookies. Hazing has always been popular in professional sports. Did you haze him at all and did you receive any of that treatment yourself?

JT: I didn’t get hazed as a rookie because, fortunately, I was surrounded by a group of veterans who were very secure with themselves and didn’t feel the need to prove anything. Like I said, Patrick Ewing claimed me as his quote unquote “rookie” and he never really asked me to do anything out of the ordinary. He saw that I had a great work ethic and that I was easy to get along with. Every once in a while, I had to get newspapers or donuts, but that was really the extent of it.

As a veteran, I didn’t really haze either; although some of the guys around me were doing it. I remember Lorenzen Wright, may he rest in peace, would steal car tires and fill cars will popcorn. Some players would make the rookies get donuts and if they weren’t warm, they’d have to get more. But I don’t believe in messing with people like that. I believed in giving people advice, mentoring them and showing them how to be successful in the league.

Image courtesy of Celtics Life.

JK: After your tenure with the Raptors ended in 2000, you had a number of stints overseas and in the CBA (Continental Basketball Association). You actually didn’t rejoin the NBA until almost five years later when you signed with the Timberwolves. Describe your journey back into the league after being away for so long.

JT: Taking a step back, in my second year in Toronto, I was playing the most minutes of my career and had done well in those minutes. During my third season, my minutes decreased even though I came into the season in much better shape and much more refined as a player. That offseason, the Raptors signed Michael Stewart to a six-year, $24 million deal and after that; management wasn’t in contact with me at all. I was so angry about it that I let it destroy me; so much so that I stopped loving the game and when free agency hit, I decided that I wasn’t going to play anymore.

When [current Raptors head coach] Dwane Casey was an assistant with the Sonics, he was consistently calling my phone and I ignored all of his calls. The Lakers, who had just won the championship, called as well and I didn’t entertain them because I didn’t want to play in the triangle. Basically, I was stuck in this immature, twenty-something-year-old mindset and told myself that basketball was stupid; that it didn’t define me. There were rumors that I was depressed. My agent asked me if I was losing my mind. It was a very uncertain moment in my life. What I really needed was a mentor to help guide me through that process, but I didn’t have one at the time. I ended up starting a business, and after about two and a half years away from the game, I decided that I wanted to play again. I began working out. I was in bad shape; I think I topped out at 302 pounds because all I was doing was playing video games and working on my business.

Not too long after that, I signed on to play for the Sioux Falls Skyforce of the CBA and that’s when I was introduced to [current Sacramento Kings head coach] Dave Joerger who quickly became one of my favorite coaches to play for. After the CBA, I received an offer to play in Spain, so I went over there to play and had a great season. They wanted to sign me to a two-year deal, but I said no because I had my mind made up that I was going back to the NBA.

I ended up going home to Minnesota, and sat in the stands to watch the Timberwolves play the Lakers in the Western Conference Finals [in 2004]. The arena that night was electric, and being out of the NBA, I missed that feeling. After their season finished, I ran into Sidney Lowe and Don Zierden, who were assistant coaches with the Timberwolves at the time, and told them that I wanted to work out with the team. I ended up training with them all summer, went to training camp with the Timberwolves and wound up making the final roster.

JK: So against the odds, you were able to accomplish your goal of making it back into the NBA. You ended up playing in the league for two more seasons with four different teams. Take us through your final seasons in the Association.

JT: I thought I had a decent season with the Timberwolves and that I was going to get resigned, but that didn’t happen, so I wounded up signing with the Memphis Grizzlies the next offseason. Then when Brian Cardinal was brought on, the team released me. After that, I had a short stint with the Atlanta Hawks. When that ended [in January 2006], I didn’t think anyone was going to sign me because it was so late in the season, but [Nets President] Rod Thorn called me and said that he wanted me to go play in New Jersey. He said that there was a strong likelihood that they’d have to face the Pacers in the first round of the playoffs and the Heat in the second round, and that the team needed a strong inside presence to guard Jermaine O’Neal and Shaq.

JK: What was it like guarding Shaq in the playoffs?

JT: It was a crazy experience. In Game 1, he didn’t try too hard. The media made a big deal out of it, saying I did a great job guarding him and so forth. But I told everyone to pump their brakes; after all this is Shaq we’re talking about. In the second game, he came out and played like an absolute monster and put all of that talk to rest.

JK: I read that Shaq kept jokingly referring to you as [Georgetown University’s] John Thompson. Is that true?

JT: He did. We were standing at the free throw line and he looks over and asks me if I was John Thompson Jr., I said no. Throughout the series, I’d be in my team’s huddle and he’d be in his. I’d look up and Shaq would be staring at me from the other side of the court, and would mouth “John Thompson” to me. He did the same thing during the national anthem before one of our games. Obviously, I couldn’t hear him, but I could read his lips and he’d be saying that. But that’s just Shaq. He’s a hilarious guy. He’s hands down one of the greatest personalities in our league’s history.

JK: Everyone knows about Kevin Garnett’s personality on the court. He’s confrontational, he’s demonstrative and in your face. What was he like as a teammate?

JT: I’ve always had the upmost respect for Kevin. He was one of the best, if not the best teammate I’ve ever had in the NBA because of his leadership and his never say die attitude. He treated practice like it was an actual game. I actually felt bad for him because I felt like certain teammates quit on him. When he was traded to the Celtics, I was so happy to see him finally win a championship. I remember when he let out that famous “anything is possible” scream; I understood the emotion behind it because I saw first-hand how dedicated he was to winning. After losses, Kevin would just stand there in the shower for long periods of time. He wouldn’t say anything. Losing just ate away at him. He hated it so much.

JK: On the flip side, what was it like playing against him?

JT: I remember when Dwight Howard was a rookie, Dwight tried to talk to Kevin during the game and KG did not say a word back to him. When he and I were standing next to each other at the free throw line, Dwight turned to me and said, “What’s wrong with this dude? Is he okay?” But that’s just who Kevin is. KG treats all of his opponents like enemies. That’s his mindset. He’s got that old school mentality. He doesn’t care if his mom is on the court. If she’s wearing a different jersey, Kevin is going to dunk on her. In today’s NBA, that type of mentality is considered to be extreme because all of the players want to hug and be friends. KG has never been like that.

JK: Did he give you that same cold shoulder treatment after you left Minnesota?

JT: Yes, he did. When I was playing for the Grizzlies, we were in town to play the Timberwolves. Before the game, I went up to Kevin to say hello and he wasn’t about it. I didn’t take it personally though. In his head, I was now the enemy because I was wearing a different jersey. I’m sure if I saw him on the street it would be all love, but not on the court.

JK: What about Latrell Sprewell? He’s another guy who has gotten a bad rep for a variety of reasons. What was he like as a teammate?

JT: He’d probably tell you he made some mistakes in several areas, but Latrell is actually a smart guy. He’d always be cracking jokes. On plane rides, he and I would play chess with each other. At the same time, he was very intense as well. He was a take no nonsense kind of guy. One time I set a hard screen on him in practice and he let me know to never do it again. Overall, though, he was a great teammate. I never had any problems with him.

JK: Moving on to your international career; you played in a variety of countries throughout Europe and Asia. For a lot of American born players, adjusting to life overseas can be difficult because of the cultural barriers. What was your international experience like?

JT: Playing overseas was really good for me because it brought me back down to reality. In the NBA, your flights are chartered and your checks are large and arrive on time. It doesn’t matter if you’re injured or if you’re sick; you’re going to get paid regardless. Your clothes are washed for you. The locker rooms are clean and the hotels are top of the line. Most players don’t appreciate how well they have it in the NBA because privilege and entitlement is all you know on the way up to the big leagues.

JK: Which country did you enjoy playing in the most? And which did you enjoy the least?

JT: My best experience was in Israel because we only practiced once a day as opposed to twice a day in most other international leagues. The weather was beautiful and the night life was very lively. The fans were some of the friendliest, most welcoming fans in the world. There were times when I literally gave my phone number to fans and after games we’d meet at local restaurants and talk. Fans would offer to pick my wife up at the airport and run errands for me. Playing in Greece was also a lot of fun because I was teammates with Bobby Brown, P.J. Tucker and Bryant Dunston. Our coach didn’t see the talent we had and we couldn’t put it all together to win, but playing with them was great. Spain and South Korea were wonderful experiences as well.

I’d say the most challenging experience for me was playing in Syria. The reason why it was so difficult for me was because I felt isolated and I was going through a divorce. Living in any country away from family and friends is tough, but when your marriage is deteriorating, basketball takes a back seat. Picking up the Arabic language was tough, and being a guy who enjoys immersing into the culture, I couldn’t do that as much as I would have liked. Plus, I wasn’t getting paid on time. But even so, that was such a great moment in my life because I experienced so much growth throughout all of that. I was lonely, but my teammates were always supporting me. They cried when I told them I was leaving Syria. I was able to develop genuine relationships with a lot of them that I’ll always cherish.

JK: P.J. Tucker went through a similar situation as you did where he was in the NBA, didn’t get re-signed and had to spend a handful of years overseas until he got another shot at reentering the league. Did you ever give him advice on how to make it back to the NBA?

JT: I didn’t offer advice because I was still trying to complete my own journey. Going from country to country, I was like a nomad. I didn’t really know how to mentor players because I still needed mentoring myself. I didn’t have a full understanding of who I was and the type of player I should be, so I couldn’t point him in the right direction because I wasn’t certain what that direction was. But P.J. is a great guy. The time I spent with him was short, but very enjoyable. I was so happy to see him make it back to the NBA. When I was playing for the Timberwolves, he came to our free agent camp. He was out of the league at the time, but he kept trying and found a home with the Suns and stuck. But that just goes to show you how many great players there are around the world that aren’t in the NBA.

JK: Transitioning to life off of the court; so often we hear about professional athletes going bankrupt. Around 60 percent of NBA players go broke within five years of retirement. It’s almost 80 percent with the NFL. Why do you think this is such a consistent trend amongst athletes?

JT: For the inexperienced, unprepared and uneducated, saving money isn’t sexy; especially now because this culture is so concerned with instant gratification. You’ve got every type of ego boosting distraction making you feel good that pulls you away from reality. The addiction to that feeling is real and it’s destroying lives. Players will spend six figures on a car and post about it on Instagram so that everyone knows how cool they are. What they don’t understand is that while the likes pile up, their bank accounts are dwindling as fast as people are scrolling through their posts. From the outside looking in, it’s easy to say that it wouldn’t happen to you, but when you’re in the spotlight and if you don’t have a plan to win, the concept of saving money doesn’t register because the big checks keep coming for the duration of your temporary career. For me, in the blink of an eye, I went from having to scrape together quarters to buy a pizza at the University of Minnesota to making $40,000 (after taxes) every two weeks in the NBA. That type of money gives you a sense of power. You feel like you’re the man and it makes you want to spend stupidly. Looking back, I should have asked more questions, but at the time, I didn’t know which questions to ask because I had never been in that scenario.

Unfortunately, I lost all of the money that I made throughout the course of my career. The culture surrounding me was in my face more often than those that tried to warn me. It influenced me to continue my ways because I probably took the advice as an attack on my ego boosting distractions. I wasn’t equipped with the knowledge on how to manage my money. When my parents got divorced, my mother had to work two jobs to feed three giant children. She didn’t have the time to teach financial literacy to us, and education is what it really comes down to. It’s not about age. It’s about experience, preparation and education. You can give a twenty-year-old millions of dollars and a fifty-year-old millions of dollars. If they aren’t properly taught how to manage their money, I guarantee that both of them will go broke.

JK: What do you think the NBA can do to better educate their players on handling their personal finances?

JT: It’s really a union issue because they are working to protect the players. I think the NBPA is doing everything they can and they continue to get better, but it’s a difficult challenge because from a young age the AAU system is giving kids certain royalties well before they’ve earned their stripes. The culture has previously molded their mindset and only explodes once they get to reap the rewards of making it to the NBA. Players are entering the league with a sense of entitlement prior to even wearing a practice uniform. It’s hard to convince them that they should invest their money instead of blowing it at the club because they don’t realize that they won’t be making this type of money their entire lives. But the majority of the time, players don’t want to think about that stuff because it’s not sexy. In their eyes, popping bottles in the club is sexy. Driving expensive cars is sexy. Buying multi-million dollar mansions is sexy. That’s just the mentality, it comes from the culture and it’s unfortunate. The experienced, prepared or educated players, though, will invest their money wisely. They’ll lead frugal lifestyles. They’ll start profitable businesses that generate additional income. They’ll teach what they’ve learned to others. Now that’s sexy!

JK: Talk about the party scene in the NBA a little bit. Especially having been a Knick, in a city like New York, I feel like there was so much temptation every time you left your room.

JT: I didn’t really participate in that life, but I’ve seen what it’s done to players. I feel like it’s a lot worse now because the party lifestyle is so much more sensationalized. But it’s exactly how it’s portrayed in the movies. As a professional athlete, everyone knows your name and they know your face. Everybody wants to meet you. At the clubs, you don’t have to wait in lines. All you have to do is make a phone call and say you’re coming through, and the club owners will set everything up for you. I think, ultimately, that type of lifestyle does not prepare you for the fall; when you retire. When your career ends, people don’t care about you because you’re not playing anymore; you’re a thing of the past. Psychologically, it’s difficult because you’re not earning these large checks anymore, you’re not relevant anymore and people aren’t asking for your autograph. Star athletes are so used to getting everything they want. No one ever tells them no. They’re constantly surrounded by “yes men” because all of their friends want to reap the benefits of being in their inner circle. Having people consistently telling you how awesome you are is a chemical addiction. Players are like modern day gladiators. Once they’re finished and forced to hang up their swords and shields, they’re no longer “of use” anymore. It’s a challenging thing to get used to.

Image courtesy of John Thomas/Twitter.

JK: Currently, you’re working with Ultimate Hoops as the National Manager of Training. Talk about some of the work you’re doing with them.

JT: I’ve always been a firm believer that I can accomplish anything that I put my mind to. I think that mindset helped me be successful in making the NBA and playing overseas. But transitioning out of basketball was a scary time for me because I was very uncertain as to what I wanted to do next. The one thing I did know is that I had a passion for helping people, which is why I joined Ultimate Hoops. Through our platform, we’ve been able to provide jobs for people who want to teach. Our long term mission is to provide much more than just basketball training. We have these first class, state of the art facilities where we can train kids and adults; anyone who wants to improve their basketball skills or get a great workout. Beyond that we want to utilize our education centers where we help athletes realize what their true value is and how they can be productive members of society.

Basketball was just one chapter of my life. I’m excited about this next chapter where I have the opportunity to mentor kids. Anyone who touches a basketball court has a place in my heart. I understand what they’re going through and the challenges they’ll face. I know what it feels like to have a coach who doesn’t understand you and doesn’t utilize your skills correctly. Statistically, seventy percent of kids drop out of basketball by the age of 13. We want to help prevent that. We want to be able to provide the type of guidance to these young athletes that I didn’t have. It’s an ambitious challenge, but we’re up to the task.

JK: I saw on Twitter that you’re very active with NBA Cares as well. Talk about your involvement with them.

JT: That’s right. A lot of those initiatives stem from our recent partnership with the National Basketball Retired Players Association. The NBRPA’s mission is to create a pathway for former NBA & WNBA players to successfully transition after our playing days are done. What you saw was a joint NBA/NBRPA event of us former players working with the youth through NBA Cares. I’m out there joking around and having a great time with the kids. Too often, people get caught up in the business aspect of the industry and forget that it’s a game. Working with the kids is a great reminder that the game is supposed to be fun; that’s why we started playing in the first place.

JK: Looking into the future, how do you see yourself continuing to impact the game of basketball?

I would never want to be a coach because those jobs are too unstable and my career path would be dictated by wins and losses rather than the progress my players would make through their journey. I want to create lasting and meaningful relationships. I want to continue being a giver of knowledge and to utilize basketball as one way to tell my story in order to enhance others’ lives. I want to empower people and help them be the best versions of what they aspire to be. That’s what I care about the most and I’m happy with the direction of my life.