Screen capture courtesy of the NBA/YouTube.

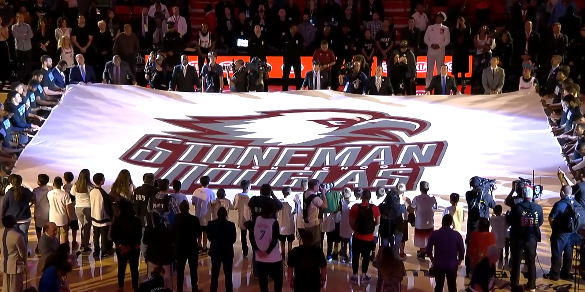

In what’s being all too common of a practice these days, the Miami Heat on Saturday held a pre-game ceremony to honor the victims of the massacre at Stoneman Douglas. In a moving ceremony, Dwyane Wade spoke of honoring victims and supporting the teenagers who are America’s conscience. Lastly, Stoneman Douglas student Alex Wind sang a moving rendition of the National Anthem.

All of this is wonderful. Honoring the victims and the Heat’s position as the pre-eminent sports organization in South Florida is further enhanced by not only doing a ceremony like this, but striking all the right notes – both teams holding a Stoneman Douglas banner, Wade’s speech, Wind’s anthem along with the moment of silence.

That the Miami Heat along with the Florida Panthers and University of Miami basketball team take time to honor victims of a shooting and it’s consigned to the also-ran area of the sports pages speaks to the unrelenting horror foisted upon citizen of this country all the time now. However, instead of devolving into a political call to action, it’s important to understand who South Floridians are.

A major part of today’s South Florida are our athletes and few athletes occupy a reverential space like Wade. But Wade is no different than many South Floridians in that he’s not from here, but he chose to be here. His story is no different than millions of others who came from somewhere else to call America’s Eden their home.

The Transplants

In the not-so long history of South Florida, transplants have arrived from colder climes to call South Florida their home. From Julia Tuttle being the only American woman to found a major city to the young men and women today passionately speaking truth to power, transplants made South Florida into a vibrant, diverse region and economic/cultural powerhouse rivaling New York and Southern California.

In 1896, after a massive lobbying effort spearheaded by Tuttle that may have included sending railroad magnate Henry Morrison Flagler oranges and foliage, the city of Miami was formally incorporated. 122 years later, Miami is the center of the South Florida region – a region including the counties of Miami-Dade, Broward, and Palm Beach – responsible for much of America’s cultural and sporting progress and success in the last 30 years.

Tuttle died two years after the incorporation and largely in debt thanks to land grants to Flagler. Today, her legacy is honored with a statue in Bayfront Park and her name on the Causeway connecting Miami to Miami Beach. And, in the tradition of South Florida being creative cauldron, the Bee Gees credit the rhythm of their car on this particular road for inspiring their hit “Jive Talkin’.”

Julia Tuttle is not the only transplant to change South Florida, but she was the first of many. In 1903, a man founded and published the Miami Evening Record. As his small newspaper gained prominence, he decided to change the name of it. In 1910, that newspaper became the Miami Herald. The man’s name was Frank Stoneman. His greatest contribution to South Florida, however, would not be that newspaper, but instead his daughter: Marjory.

The Grande Dame of the Everglades

Despite graduating from Wellesley College in 1912 and being one of the original suffragettes, Marjory Stoneman Douglas was stuck in New England and married to a con artist. She was convinced to give Florida a try, and her father gave her a position at the Miami Herald in 1915. She wrote when she arrived, Miami was “no more than a glorified railroad terminal.” At the time, the city’s population was less than 5,000.

As a writer for the Herald, she continued her work as a suffragette and wrote a short story largely responsible for the end of convict leasing in Florida (the practice of using prisoners as “slave labor”). Increasingly, her writing became focused on animals and the environment. The targets for her ire were poachers slaughtering the roseate spoonbill, great blue heron, sandhill crane and other tropical birds for their feathers.

The cause near and dear to her heart, however, became Florida’s Everglades. In 1947, she wrote The Everglades: A River of Grass. The first line in the book, “There is no other Everglades in the world”, characterizes the uniqueness of our lives here in South Florida. Of course, the book sold out in its first printing, and of course, now everything Everglades also contains the phrase “river of grass.”

Throughout the rest of her life, the name Marjory Stoneman Douglas was synonymous with Everglades preservation and restoration. Her two main foils were the Army Corps of Engineers and Big Sugar – a consortium of sugar cane conglomerates possessing no redeeming qualities whatsoever that contribute massive sums of money to politicians so they can make it easier to dispose agricultural waste directly into Florida’s waters for us South Floridians to then consume.

At 79, she organized the successful resistance to a proposed Everglades Jetport. Her stirring opposition even bent the will of Richard Nixon, a proponent of the project.

No matter the money or the military might, this woman, described as having half the physical stature as the men she addressed, she spoke and wrote with distinct authority. During her life (she lived from 1890-1998), she saw the growth of Miami the city and South Florida the region from a small, isolated area to being one of America’s great success stories.

At the age of 103, President Clinton honored Marjory by awarding her the Presidential Medal of Freedom. He spoke of her unyielding spirit in defending the Everglades. That same day, she was in the room when the President signed the Brady Bill, mandating background checks for anyone looking to purchase a firearm. In South Florida’s long history of transplants making an impact Marjory Stoneman Douglas is especially revered.

Dwyane Wade: The Latest Transplant

Kids should have heroes. Dwyane Wade is one of those heroes. This young generation of South Floridians is unlike previous generations with their sports consumption. Unlike transplants, their teams are the local teams and as they’ve grown up one team has been especially successful and relevant: the Miami Heat.

Basketball is more popular among young people than other major sports, and first among South Florida kids’ sporting heroes is Wade. The post-millennial generation is defined roughly as born after 1998. Wade came to Miami in 2003 and the kids grew up with him. They were young in 2006 when Wade pinballed through the Mavericks to win Miami’s first professional basketball championship. They were impressionable tweens during the Big 3 era and devastated when D-Wade left Miami for Chicago.

There was jubilation when Wade returned to Miami. Wade is no wallflower of a star. He’s active in the region and has several charitable initiatives helping at-risk youth develop intellectual and social skills.

Wade is no stranger to activism, either. He’s been on stage at the ESPY’s speaking about change and leads efforts to improve relations between community members and the police. Wade is also a victim of gun violence. His cousin was killed in Chicago. He knows the pain of losing a loved one to what Bobby Kennedy called the mindless menace of violence.

In that sense, the students of Stoneman Douglas and Wade share a bond they never should have to share. In an even more raw sense that exemplifies Wade’s connection to South Florida’s youth and illustrates the very personal nature of this tragedy, one of the victims, Joaquin Oliver, was buried wearing Dwyane Wade’s jersey. A week before he died, friends and family saw how excited he was that his favorite player was returning to his favorite team.

Wade spoke to the Miami Herald and noted how this was one more example of how bonded he is to South Florida while ruminating at another reminder of the fragility of life. Wade also posted on twitter that this story is yet another reason why he won’t shut up and dribble. Quite fittingly and unsurprisingly, Wade is using his voice to elevate the voices of these amazing young South Floridians seeking to affect change.

The Homegrown South Floridian

Parkland sits right on the edge of the Everglades, it’s one of Broward county’s more affluent areas and its meticulously manicured cul-de-sacs are South Florida’s version of the American dream. Barrel-tile roofs and palm trees dot the area, it was named one of America’s safest cities. There’s a reason people come to Parkland.

In the great tradition of transplants in South Florida, Parkland is just another example of a place people come because, well, why wouldn’t you? South Florida has beautiful weather all year, our flora and fauna are the best in the world, and the ability to literally do anything is unmatched. Where else can you play outdoor sports in January and possibly be too hot? Listen to the people of South Florida speak, and there is a collection of accents literally spanning the world.

This is the only place where six people can speak to each other and each continent is represented. Our diversity is our strength, and we love it.

This region has grown in prominence so quickly and sports noticed. In 1980, the only professional sports team in South Florida was the Miami Dolphins. In 2000, South Florida counted the Dolphins, Marlins, Heat, and Panthers as major sports franchises. In a couple years, Miami will have an MLS team. There will be a difference, though.

Unlike previous generations of South Floridians, most of South Florida’s children are from here and in many cases so are their parents. The South Florida transplant’s contributions are slowly, steadily being replaced by those from its homegrown people. These kids and young adults feel immense roots to their home, and unlike the older generations of South Floridians, support their local teams. South Florida, once a community where the question, “Where are you from?” would start a conversation, now speaks about its sports the way New Yorkers, Bostonians, and other, more traditional markets do even though we pride ourselves on being nothing like anywhere else in America.

That last point is the essence of this place. South Florida truly is like nowhere else in America. I’m biased, but we do everything better. From the art-deco hotels of Ocean Drive to the Gilded Age mansions of Palm Beach, South Florida produces excellence at every turn and does so with more flair than anywhere else.

It’s no surprise that athletes live down here and yearn to play for our teams. Ask yourself, where would you rather be – Miami or Pittsburgh?

However, despite the aesthetics of the region along with our institutions, one thing about South Florida was a bit hidden prior to the tragedy at Stoneman Douglas: the awesomeness of our kids.

The generation of kids produced in South Florida are the best in our nation. They are bright, articulate, conscientious, and unbelievably accepting. As a former teacher still involved in athletic coaching, they amaze me every day with their resilience and persistence about doing the right thing.

I’m not the least bit surprised these kids turned their anguish into activism, and that their activism went viral. Nor am I surprised at how other schools walked out in solidarity, including students at West Boca Raton High School making an 11-mile march from their campus to Stoneman Douglas. There is a palpable sense of outrage here, and in the tradition of South Floridians getting stuff done, these young people are being the role models adults should be.

The journey for the survivors is a long one as the physical scars heal. There will be considerable psychological trauma for years to come for these young women and men. However, at Stoneman Douglas High School, inside the courtyard in black letters is a quote, “Be the change you wish to see in the world.” For too long, Gandhi’s exhortation was just one of those things schools put on walls in unyielding attempts to motivate students to exceed what they expect of themselves.

In the fortnight since Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School was forever changed, these students have followed in the tradition of Julia Tuttle, Marjory Stoneman Douglas, Dwyane Wade, and countless other South Floridians – they are changing the world.